We’ve all seen the Shark Tank pitches starting with a flash-mob style dance, followed by a Colgate smile in a suit with impressive articulation and conviction, or the Hollywood scenario where a scrappy guy in a t-shirt interrupts a board meeting with a passionate speech gets a standing ovation, the job and the girl. This is what success looks like, we are led to believe. Confident persuasion is the key to get us what we want. I call b-s on that. Many confident people aren’t very humble and whilst humility may not be as sexy as confidence, it’s the long-term winner in my book, especially for start-up founders.

I used to attribute my affinity for humility and modesty to my Swedish heritage, where a phenomenon called Jantelagen (Law of Jante) runs deep. It’s in essence a common code of social disapproval for those who are seen to beat their own chest too much or who brag about their personal wealth or success. It’s the reason Swedes are uncomfortable talking about money and income, and why we live for concepts like “lagom”, or just enough. However I've learned over the years that humility isn't just a quirky Swedish characteristic but can also be a great indicator of intelligence, growth potential and, ultimately, success.

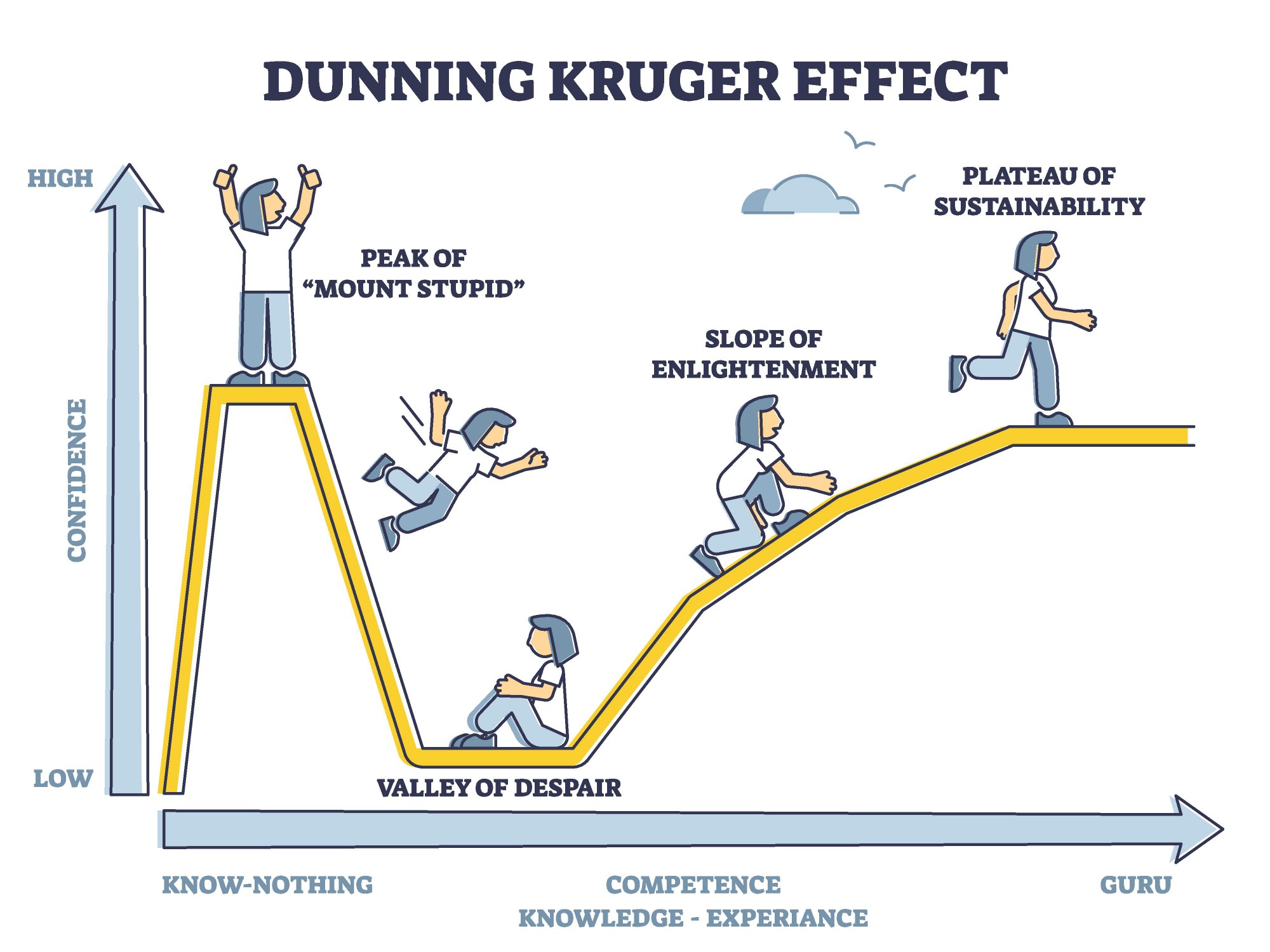

To me, humility is not about being overly cautious, insecure or having a feeling of inferiority to your peers. Quite the opposite actually, and I believe it can be shown with the Dunning-Kruger effect.

Named after social psychologists David Dunning and Justin Kruger, it illustrates the cognitive bias of illusory superiority, i.e. people’s inability to realize their relative ignorance. By plotting confidence against competence, it shows how people’s lack of self-awareness to their own low competence can generate high levels of confidence. Only when you reach a certain level of competence will you truly understand how much more you have to learn. As such, we as humans probably reach peak humility in the “valley of despair” where we grasp our limited understanding and how much more we need to learn to achieve competence. Humility can thus, arguably, be a baseline measurement of someone’s competence. In other words, are you smart enough to realize how incompetent you are, yet have the courage to carry on? If not, the confidence might spill over into arrogance, and according to Dunning-Kruger, if you meet a highly confident person, they are either very incompetent (and likely arrogant, I’d argue), or a guru.

Jim Collins, author of the widely acclaimed book “Good to Great” argues that Level 5 leaders, the highest level of leadership and a label only bestowed on those who are truly great, display a powerful mixture of personal humility and indomitable will.

Those leaders are running big corporations, you might counter, and to build a start-up you have to be bold and fearless. If I am not very confident in myself, how can I expect anyone else to place their confidence in me?

Good points, but I argue you don’t have to be the slick presenter whose voice never trembles to get ahead. In my role as a Partner in an early-stage venture capital fund, I meet start-up founders on a regular basis who are at a stage where they are trying to figure out their product-market fit. This is, in my opinion, one of the most exciting times in a company’s growth cycle but also one that is riddled with not only known unknowns, things we know we do not know, but also plenty of unknown unknowns, things we don’t know we don’t know. As such, anyone walking into a meeting with an early-stage start-up should not expect to see a perfect and final business model being presented. Whilst there hopefully are clear signs of traction, the probability that future adjustments and pivots to the business model might be necessary is high. Founders that are too salesy and try to give the impression that everything is perfect thus lose credibility with me quite quickly. There will definitely be chinks in the armour and my team and I will likely find them. Founders that instead are open with the gaps that have not yet been filled, traction that has not yet been obtained, questions that have not yet been answered - there always are - come across as realistic, aware and, in my view, humble. Discussions with these types of founders quickly turn from “where are the issues” to “ok, how do we overcome them?”. Know-it-alls usually get shot down in flames, whereas humble founders receive empathy and support.

Launching your own business is incredibly hard. Finding one or two kindred spirits to join you on the journey, surrounding yourself with great advice, support, partners, investors, etc is rarely easy. Even if your business gets traction, it usually doesn't get any easier. It's hard to be the right person to start a company and also be the right person to manage it when it has 1,000 employees because you have to be different types of people. No one is an expert at everything, so you have to be able to adapt and evolve. If you’re curious, open-minded, welcoming, adventurous and shameless about getting feedback you’ll set yourself up for situations where you will grow and develop fast, for the benefit of yourself and your business. All of the abovementioned traits are, in my opinion, rooted in humility.

In my meetings with founders I never expect anyone to have answers to all my questions. Instead, one of the things I look for is their clarity of vision, how they address and approach their known unknowns, and how adaptable they are to changes. Whatever they are working on, a sense of superiority will make them worse at it. The moment they think they have it all figured out, progress stops. Humility, on the other hand, will make you gritty, resilient and progressive. It will push you to continue to advance and improve by reminding you how much more is there to discover.

To all start-up founders out there: tone down the sales pitch and skip the superlatives when describing yourself. Instead, be open and comfortable with who you are, show humility for what you have achieved thus far and be smart enough to realize how much more there is to learn.