Stephen Turban lives in Ho Chi Minh City and works for Fulbright University Vietnam. Sign up to follow his writings here.

Disclaimer: This is a personal experience from an American based in Ho Chi Minh city who just flew back from the U.S. and went through a COVID-19 testing procedure for immigrants. The article does not reflect any of Vietcetera’s viewpoints regarding the topic.

Earlier today, I went through the most intense immigration experience of my life. Over the course of five hours entering Vietnamese immigration, I was assembled into a quarantine zone of hundreds of people coming from the US, moved from the airport to a COVID testing clinic, tested, and then sent back to my home to self-quarantine until I receive the results (I am still waiting). Even with negative results, I’m asked to undergo “self-monitoring” for the next 14 days.

Below, I describe step-by-step what happened to me. Looking back, the Vietnamese government did a better job than I expected given the last minute announcements with this testing and immigration. However, there were several ways the process could have been more smoothly communicated, especially to English-speaking foreigners. Here, I share some tips for travelers who have trips coming up to Vietnam.

UPDATE 9.30am March 18th Vietnam local time: To staunch the spread of COVID-19, for 30 days from March 18, 2020, Vietnam will not be issuing visas to any foreign nationals. Travelers from countries with visa exemptions will only be allowed to enter if they can show medical papers certifying they are free of the virus. All incoming travelers from the United States, European and ASEAN nations must undergo medical checks and 14-day quarantine upon arrival in Vietnam.

Friday, March 13, 2020: Finding out that the borders of Vietnam were closing

This past Friday, I was in San Francisco for a few meetings and PhD visits. I was talking with a friend in the Mission when I received a concerned message from my friend, Trang with a screenshot of the Vietnamese government announcing that they would deny issuing visas for all nationalities from March 15 to April 15, 2020.

The press release described “visas.” However, I wondered if it also would affect foreigners who lived full-time and worked in Vietnam with a work permit, as I do. So, I called up the hotline number and spoke directly with one of the staff.

As they described to me then, “By 10:00 AM, Monday, March 16, the borders will close to anyone who is not a Vietnam citizen.” Though I wasn’t 100% sure if this was accurate, I thought the risk was too high. My work was in Vietnam. I didn’t want to get shut out of the country for a month, and likely many months. I needed to fly back.

Friday – Sunday, March 13-15: Flying to Ho Chi Minh City through Taiwan

At the cafe, I booked the next flight back to Ho Chi Minh City, which was 1:00 AM that night, March 14. It was scheduled to arrive at 10:00 AM in the morning on March 15 with a transfer in Taipei.

When I arrived at the airport, the airport staff did not mention any of the travel restrictions – making me think that they had yet to be notified of the updates. The travel itself was uneventful, except for the 80% of seats that lay empty.

Sunday, March 15: Arriving at Tan Son Nhat Airport & queuing through immigration

I arrived at Tan Son Nhat airport at the expected 10:00 AM time. Immediately, when I entered the area for immigration, I sensed this would be a struggle. There was a long, bunched crowd coming out of what usually constitutes the entrance. There were at least 150 people in the crowd trying to get through the first part of what appears to be a multi-step journey to go through immigration and the health check.

To the side of the line, there were a number of booths representing different airlines. The sign reads “on-going transfers,” but it was clear that the booths were for individuals who didn’t want to risk the testing and quarantine. It was filled with mainly Europeans booking tickets back out of Vietnam.

This first line was for every passenger, regardless of previous travel history, to submit their health declaration form. This health declaration form asked questions about name, contact information, flight and seat information, as well as symptoms. After waiting in line for about 45 minutes, I was second in line to talk to the staff. The woman in front of me went first, and the staff asked, in Vietnamese, where she had come from. She said that she had only been in Taiwan. For her, they pointed towards the normal immigration lines in the distance. Because she had come from a country with few COVID-19 cases, she entered Vietnam within minutes.

Finally, I got up to speak to the masked airport worker. Again, the question was asked: “Where are you coming from?” When I told him the United States, he pointed to a large holding area, enclosed with barrier tape and the sign “quarantine zone.” He handed me back my medical declaration form. In the waiting area, roughly 100 to 200 people were waiting in chairs and on the floor.

The airport was packed from all the confused passengers.Because I speak Vietnamese, I’d begun to ask people what was going on. As far as I’d read on the internet before I’d left, only people who were coming from a Schengen Area country would be quarantined. People coming from the US would be fine. However, as I spoke with people, the consensus grew that the Vietnamese government had issued a change the night before, as I had been flying across the Pacific. Now people coming from the US would also be tested and quarantined.

Being in the holding area was a mixture of confusion and boredom. There was little communication to explain to the people what they were waiting for and why. There was, however, an entrepreneurial pair of women who had set-up a booming business in sim cards.

Another picture of the immigration confusion at 10:30 AM this morning After about 45 minutes of sitting, a woman in a uniform began to announce something in Vietnamese that I couldn’t catch. Immediately, a small groundswell of people began to follow her, some running to be the first to move. Were we going to go through immigration? I wondered.

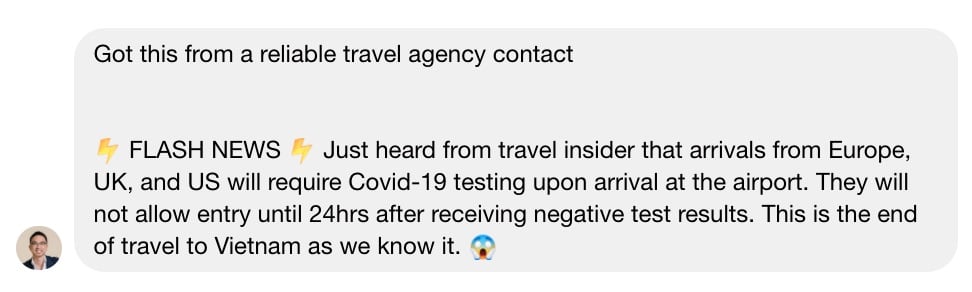

It was at about this point, right after getting my sim card back in, that I received a message from my friend Hao Tran about entering into Vietnam.

For me, this travel agency turned out to be partly right and partly wrong. I did eventually get tested for COVID-19. However, I was free to return to my home to self-quarantine immediately after the test result.

At this point, however, his message was the best information that I had. The only other information I’d received was when I asked another airport worker whether people would be self-quarantined or quarantined in groups. He told me that he thought people would be quarantined in groups; but then when I asked whether this was true for people coming from the US, he backed down. What was consistently true was that there were more rumors than truth at the airport. Travelers and staff readily gave you both.

I began to follow the groundswell as they moved into what I disappointedly found to be another holding zone, surrounded by barrier tape. This again seemed to have about 150 people, with about 20-30 foreigners making up a significant minority of the population.

It was about at this point that I met my new COVID-immigration companion, Billy. Billy heard me speak Vietnamese to one of the officials, trying to help a British couple get information on leaving Vietnam, and he introduced himself. He was a young, Vietnamese-American from the Bay Area who was coming to Vietnam for a few months. He also hadn’t realized that testing would be required or a potential quarantine.

For the next hour and a half, Billy and I loitered around this second holding area, now only feet away from the immigration entrance. Finally, we saw a female staff member come out and begin to read out names. After hearing their name, people would go to the immigration lines and be whisked away to the COVID-19 testing center. We’d learned at that point the center was in Tan Binh district, a ten-minute drive away.

We waited and listened, but didn’t hear our names. So, again we waited, this time for only twenty minutes. Again, she came out and read some names.

At this point, I began to wonder where this list of names was coming from. After all, Billy and I had just been standing in the crowd. Were we supposed to submit something to get on this list? So, I went up to one of the staff and asked how we could sign up for the list to leave. She said, “Have you given me your health declaration form?” For which I shook my head no; indeed, no one had told us that we were supposed to. It’s possible there had been an announcement in Vietnamese, but there had not been one in English.

This was the first of many moments in which the entrance process was made particularly difficult for non-Vietnamese speakers.

After talking with her, Billy and I approached all of the other foreign-looking people in the area to submit their health forms. They thanked us for the update and went to hand-in their forms. Again, we found a place to stay and waited.

After about thirty minutes, the woman came out with a long list of names. She walked to the front, where the immigration guards were, and begin to read off the name at a slow pace. At this point, the 150-odd people were surrounding her.

People waiting behind the immigration line for their names to be called. Thankfully, Billy and my name were called early, and we went through the immigration line. Quickly, we passed through and went to the baggage claim to pick up our bags and then take the bus to the testing center. As I walked out, I told the staff worker thank you and “cố lên” (a cheer to keep her spirits up). She smiled, but then told me that luckily this would all be over in a few hours. By noon today, she said, the borders would close for those trying to enter Vietnam.

Sunday, March 15: Traveling to the COVID Testing Center

She walked Billy and me down the steps to get our baggage. Then, we made a right-hand turn and moved to a third waiting area for the busses. We quickly realized there would be no “busses,” and instead there were 16 seater vans waiting for us.

At this point, Billy added a post to his Instagram story, which captured well our current state.

To date, I’m not 100% sure if that information about the border closing is true or not. I haven’t seen a confirmation in the media yet.After about thirty more minutes of waiting, now about 1:00 PM, our names were called again, and we got onto our vans.

Vans taking us to the COVID testing center.Sunday, March 15: Getting tested for COVID-19

When our van arrived at the COVID-19 center, I was surprised to find a remarkably calm looking building with only a few guards standing outside of it. The only indication that this building was being used for testing were the few people wearing nursing scrubs and the sign that said “quarantine zone.”

Entrance to testing clinic.There were only two vans and roughly 12 people going through the testing process. We were asked to leave our bags out front, though we could take our backpack. The consensus among the foreigners in the group was that we would both test here and sleep here overnight. One man called his wife to tell her that he’d likely be back tomorrow (which turned out not to be true).

Nurses instruct us to wash our hands, disinfect them, and replace our facial mask. We are then asked to enter the testing center. To my pleasant surprise, the testing center was clean and well-run. It appeared uncrowded and the staff seemed prepared.

Inside look at the COVID-19 testing center Next, we sit down, and the staff there asked us to fill out a form. Unfortunately, the English form was not well translated, so I began to work with the staff to figure out the meaning of some questions. Ultimately, I helped them draft out a new form using English.

Once we finished the forms, we headed to the back of the clinic where the testing takes place. The test itself was remarkably quick, simply a quick swab from our nose and the back of our throat. Only thirty minutes after arrival to the testing center, we are told we can depart to our homes.

What’s odd is how few instructions the staff gave us at the end. They do not tell us how we will be contacted about the results, if at all. Nor do they say whether or not we have to self-quarantine if the results show negative. The staff gave all of the non-Vietnamese a colored hand-out in English, but the hand-out doesn’t provide clear instructions either.

As the foreigners spoke amongst ourselves, it seemed clear that we should all self-quarantine ourselves until the results get back. But, the English handout that the staff gave us was especially vague as to what we should do if our results are negative. In fact, the hand out doesn’t even use the word “quarantine,” instead it is translated as “self-monitor at home.”

A set of instructions before we leave.So, by 3:00 PM, I was on a Grab back to my apartment in District 1. Five hours had passed, two forms had been filled, and one COVID-19 test had been taken. Yet, I was still going home. Something I didn’t expect to be doing so quickly.

Though I am impressed generally with how well the process went, it seemed clear to me the lack of English speakers may lead to some confusion. The handout, for example, is not clear as to how mandatory the self-quarantine is. As well, the English language forms were not well translated, I assume most people didn’t fill them out entirely.

In my mind, there is a possibility foreigners entering Vietnam may not clearly follow the Vietnamese government’s orders to self-quarantine. A big reason is that these orders are made in a way that is difficult to understand if you don’t speak Vietnamese.

With that said, for such short notice, I believe that the government has done a generally good job of testing and isolating potential COVID carriers. The fact that an order could be made while I was flying and a process built out in that time is a testament to the competence of the government and its commitment to public health.

All in all, I’m happy to be done with the process. As I write this in my house, awaiting my COVID results, I’ve realized it simply feels good to be home.

“The process I went through entering Vietnam on Sunday, March 15 involved three stages. First, I entered the immigration border and was sorted based upon the country of recent return travel. Because I had come from the US, I was sorted into a group that was sent to a COVID testing center. Second, the airport staff transported us to the COVID testing center where we did a quick test using swabs of your nose and mouth. Third, we were allowed to go back home to self-quarantine and await results. The expectation is that we self-quarantine for 14 days. As I’ve learned travelers coming from Europe, South Korea, Iran, and China will be mandatorily quarantined in government facilities for 14 days.”

Related Content:

[Article] Coronavirus in Vietnam: When Breath Becomes Terror

[Article] Proper Etiquette To Remember When Traveling Vietnam