Francois Bibonne is an independent filmmaker who has released a documentary on Vietnamese classical music titled “Once Upon a Bridge in Vietnam.” The film is the result of Francois’s 15-month journey in Vietnam, exploring and experiencing Vietnamese music and its people and culture.

Four years ago, Francois used to work for a big classical music label as an intern. When he was assigned to plot the schedules of the different orchestras and artists, he saw many cities in Asia but nothing from Vietnam. That’s when he started to wonder if there was classical music here.

“I felt something in my heart and realized I had to investigate the classical music scene in Vietnam,” Francois told Vietcetera. “I knew I needed to meet the orchestras, show it to the world, show Vietnam as a beautiful country with great musicians, and show classical music to the world through Vietnam.”

Here’s what Francois had to say about music, film, and his deep connection to Vietnam.

How did you discover your passion for film and classical music?

I’m new in the industry. I learned literature and history, not filmmaking when I was still in university. In 2018, I came to Vietnam with my parents and my brother for the first time. I borrowed a small camera from my dad and made a video to remember our trip. I enjoyed it very much and felt something new.

At that time, I wanted to be a pianist and practiced every day for 5-6 hours. I also worked for a music school as a freelance video maker and became passionate about doing interviews. Eventually, my passion for classical music married my passion for video making. Now, my life is dedicated to making documentaries.

How does music impact a film?

The rhythm is very important, and the silence is as well. A movie is like a music score, with rhythms, phrases, and accents. I like to speed the footage of the documentary in connection with the speed of the voice of an interview. For example, when someone stresses a word, I change the image of the documentary. Sometimes, I like to let the footage speak, so I put a silence phase which enables the film to “breathe.”

There are many examples. These tools allow me to make music even if I don’t play piano anymore. It’s very important for me because it’s my strength: When I edit the documentary, I play the piano somehow. I like to say that I put rubato in the rhythm of my films - meaning that the tempo accelerates, then slows down. This is definitely something that comes from classical music and doesn’t exist in the other genres of music.

We heard your grandmother was Vietnamese. Tell us about her influence on you?

It’s a spiritual influence because we never really spoke of Vietnam. A few words in Vietnamese for fun, some Vietnamese dishes and stories, that’s it. But I was very proud of her and our relationship was strong because I didn’t know my other grandparents. At school, I liked to say that I’m quarter Vietnamese. It was a beautiful difference for me, and in France, people really like Vietnam.

But why did you decide to make a documentary on Vietnamese classical music?

I wanted to be out of the box and create a pleasant atmosphere between classical music and Vietnam. Classical music is a genre of music for rich people. But Vietnam’s energy brings hope to make people interested in classical music. When COVID-19 hit, Western countries were stuck, but Vietnam was free to develop new music projects and think more about music, like a big incubator. I felt like being the center of the world during my trip to Vietnam because we may be the only artists to do so many activities in 2020-2021. So the documentary was a good decision.

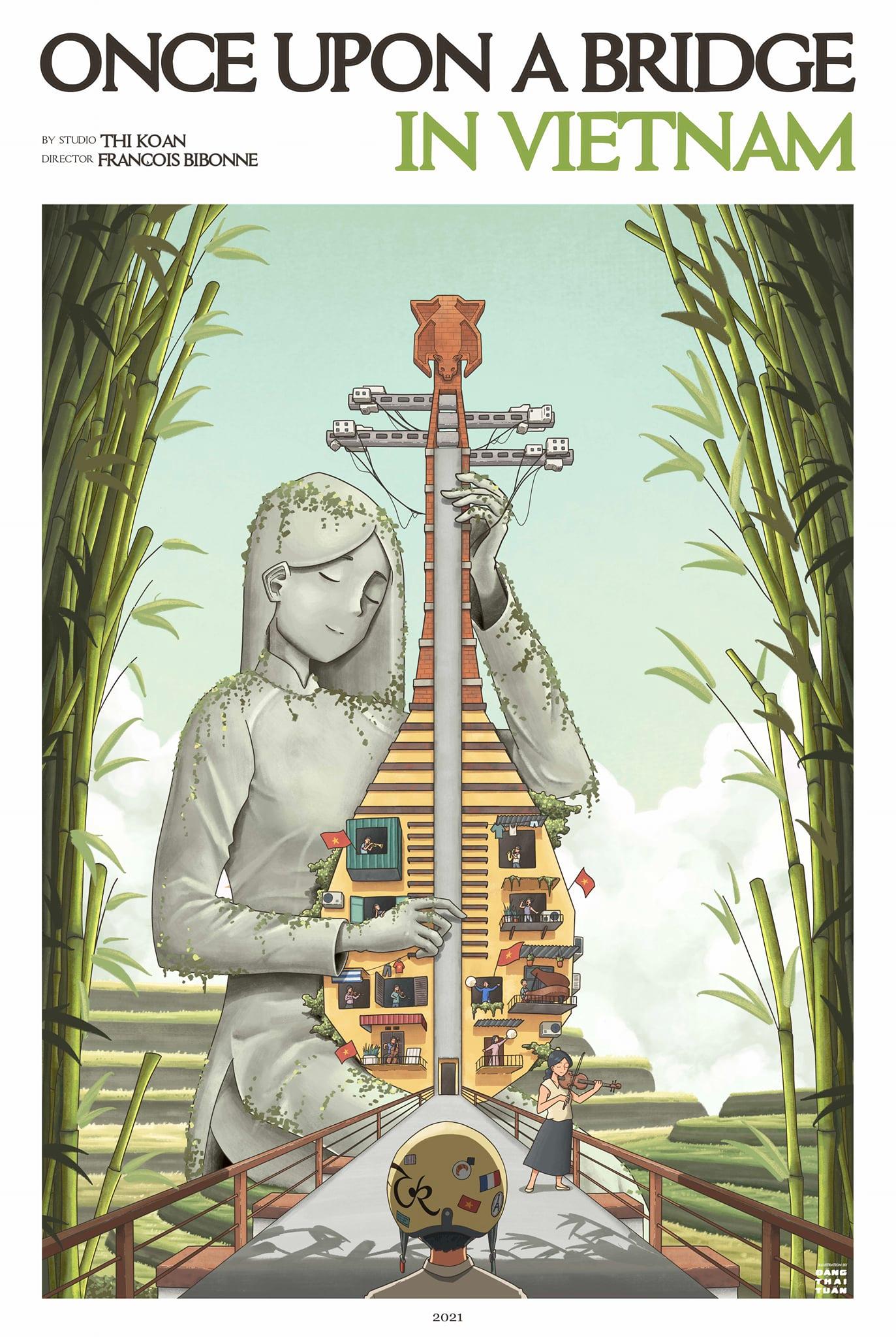

Why did you name your documentary “Once Upon a Bridge in Vietnam”?

The bridge is a metaphor for several meanings: in music, it’s a structure that connects the chorus to the verse and it’s a part of the violin that supports the strings. In architecture, it’s the bridge, so it’s the Long Bien bridge in my documentary. It also meant the bridge between France and Vietnam, the past and the future, the traditional music and the Western classical music. To such an extent, I consider myself a bridge between Vietnam and my grandmother, who left her country in 1954.

What’s the most challenging part of making this film?

I had psychological difficulties because I came alone to Vietnam without a budget and sponsors. But many musicians helped me in Vietnam, and I started to believe in my quest. Phan Thuy (ty ba musician), Honna Tetsuji (music director of the Vietnam National Symphony Orchestra), Luong To Nhu (pianist), and many other musicians gave me hope. They became my mentors.

Why is classical music not as popular as many other genres of music?

To learn classical music, you need to learn music theory, so you need a well-trained teacher and institutions with big budgets. It’s the same story for orchestras and events. Moreover, instruments like the violin and the piano imply years of training for the technical level, which means a lot of time for a passion that doesn’t really pay money.

To listen to classical music, you also need to be interested in it, which costs time because it’s not often easy to listen to. This is true for contemporary music and modern music: most people are nearly unknown these genres of classical music, even in Western countries. People like to entertain and most don’t see classical music as entertainment. My documentary wants to change that as well.

What do you think of Vietnam’s music scene?

Vietnam’s music scene is very different. It incorporates Western classical music and traditional Vietnamese music, instruments from Europe and instruments from Vietnam, Vietnamese language (ca tru, quan ho…) and dances with costumes. This is not only folklore but also the future: people create songs with traditional instruments. For example, Phan Thuy made a part of the soundtrack for the documentary. This character is the most important in my documentary; she is the allegory of my documentary.

What’s next for you?

I want to screen the documentary in many places and do more documentaries about Vietnam through music adventures. I already screened it in Paris in April, and musicians from the Viet community played to open the event. This concept of music event and screening will also happen in New York City on May 4, with pianist Quynh Nguyen playing right after my screening at the Hunter College in Manhattan. She’s a fantastic pianist who represents the bridge between America, Vietnam, and France. In October, we will collaborate in Hanoi for another documentary - she will play with the Vietnam National Symphony Orchestra. Please look forward to this event!