When fireworks light up the skies of Vietnam during New Year’s Eve, a familiar melody drifts through city streets, echoes from shop speakers, and hums in family gatherings and TV countdown specials. It’s not a Vietnamese folk tune, nor a global chart-topper from recent years. It’s Happy New Year - a bittersweet ballad by ABBA, the iconic Swedish pop group of the 1970s. Strangely enough, this song has become a New Year’s ritual in Vietnam.

Played in karaoke bars, classrooms, radio programs, and even in farewell videos made by hospitals and schools, Happy New Year has become something of a seasonal anthem. But how did a melancholic tune from a distant European band take such deep root in Vietnamese cultural memory?

The answer lies at the intersection of history, diplomacy, and an unexpected emotional resonance.

The morning after the party

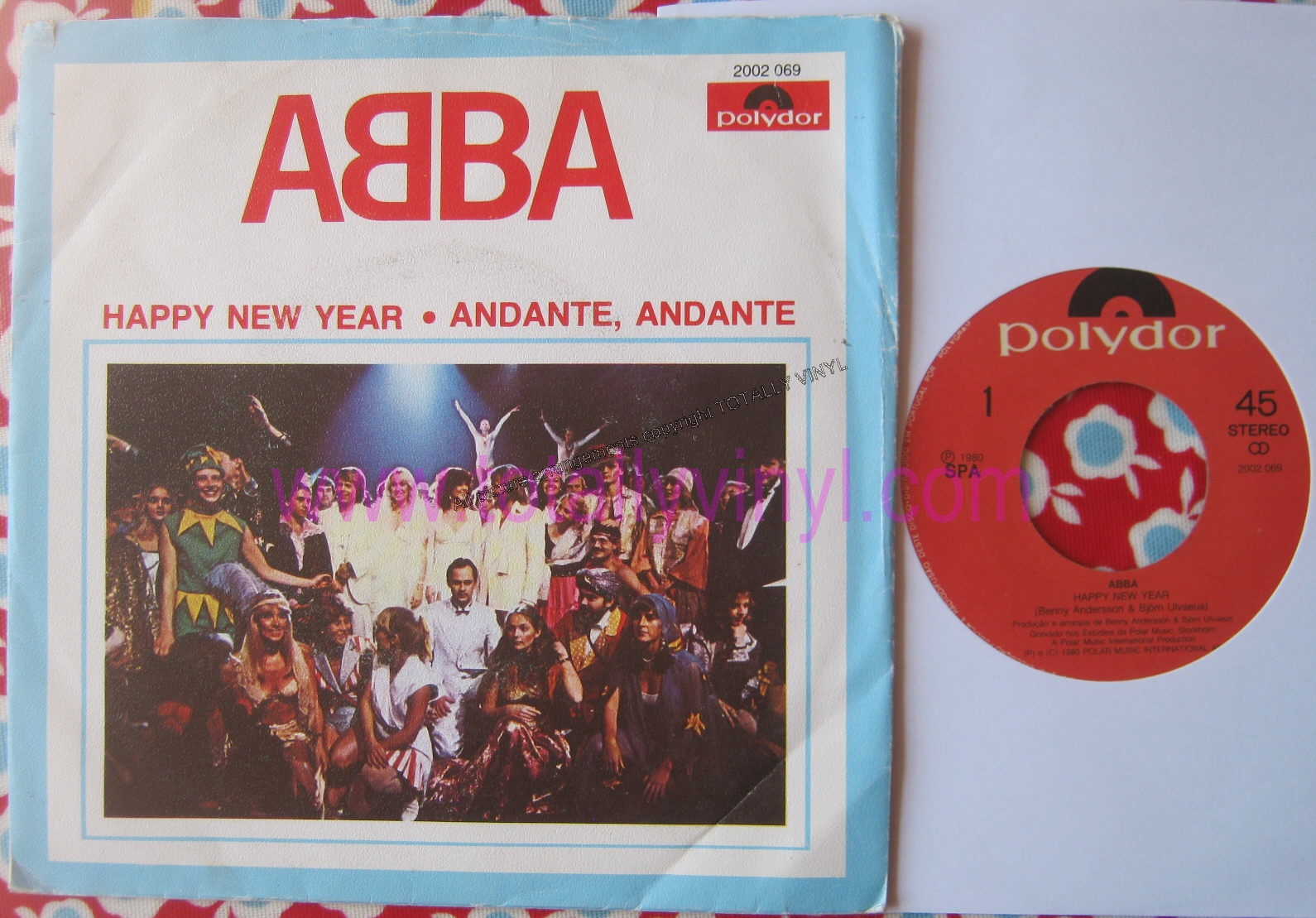

Happy New Year was recorded in 1980, right as ABBA, once two married couples, was beginning to fall apart. The divorces of Agnetha and Björn, then Benny and Frida, cast a long emotional shadow over the group’s later music. Though the song opens with cheerful piano chords and a festive title, its lyrics tell a different story: “No more champagne, and the fireworks are through. Here we are, me and you, feeling lost and feeling blue.”

It’s not a celebration. It’s a quiet morning after the party, filled with sorrow, uncertainty, and fragile hope. In the context of the world at the time with global economic downturns, political instability, and the lingering trauma of war, the song captured the feeling of standing at a crossroads, unsure of what the next decade would bring.

When it was first released, Happy New Year received little attention. It ranked modestly on European charts and wasn’t even released as a single until 1999, nearly two decades later, as the world welcomed the new millennium. Yet in Vietnam, the song found a strangely fitting home.

Sweden, Vietnam, and a rare friendship

To understand why Happy New Year became so beloved in Vietnam, we have to go back to the country’s unique diplomatic relationship with Sweden.

In the years following the end of the Vietnam War in 1975, Vietnam faced a difficult post-war period. The United States imposed a trade embargo that lasted until the mid-1990s, and many Western countries followed suit. As a result, Vietnam’s international ties were limited, and most of its partnerships were with fellow socialist countries such as the Soviet Union, Cuba, and members of the Eastern Bloc. These relationships were less a matter of free choice than of necessity, shaped by Cold War geopolitics, ideological divides, and the limited diplomatic options available to Vietnam at the time.

Sweden stood out as a rare exception. In 1969, amid growing global anti-war sentiment, Sweden became one of the first Western nations to establish full diplomatic relations with the then Democratic Republic of Vietnam (North Vietnam), well before the reunification of the country in 1975. This was not merely a symbolic gesture.

In the following decades, Sweden invested heavily in Vietnam’s reconstruction, funding major infrastructure and healthcare projects such as the National Pediatric Hospital in Hanoi and the Bai Bang paper mill. The latter was so extensive that it led to the creation of a Swedish-style village, complete with wooden cabins and sauna spas, nestled in northern Vietnam. Swedish experts lived there for years, some eventually settling down with local families.

Along with the engineers and doctors came something else: music. ABBA’s songs, carried over on cassettes and radios, entered Vietnam not as forbidden Western pop, but as cultural gifts from a trusted ally. At a time when most foreign music was restricted, ABBA was an exception. Their vibrant outfits and upbeat rhythms offered Vietnamese listeners a glimpse of a more colorful world beyond ration cards and dim streetlights.

A misunderstood message, or a perfect match?

Interestingly, most Vietnamese listeners in the 1980s did not speak English or Swedish. The song’s underlying sadness about personal heartbreak, the loss of idealism, and anxiety about the future largely went unnoticed. What Vietnamese listeners heard instead was the uplifting melody, the chorus repeating Happy New Year, and the hopeful sound of voices singing in harmony. For a country just beginning to recover from war and facing a future full of uncertainty, that was enough.

But over time, as translations emerged and people came to understand the lyrics, the meaning resonated even more. Because in truth, Happy New Year doesn’t mean pretending everything is okay. It acknowledges feeling lost, facing an unknown future, yet still wishing for peace, connection, and courage to keep going.

That duality, sorrow and hope, echoed the emotional landscape of post-war Vietnam. It was a country emerging from decades of war, still uncertain about the road ahead, yet determined to rebuild, to reconnect, and to believe in renewal.

In the end, Happy New Year belongs not just to ABBA, but to everyone who finds comfort in its notes. In Vietnam, it has always meant something deeper: a moment of reflection, a quiet pause before stepping into another year.

And perhaps that’s the beauty of music - it can be sad, joyful, and hopeful - all at once.