Phuc Van Dang is an artist and storyteller who moved to Denmark when he was only nine. He now lives in a converted former prison that has become a cultural hub in the central Danish town of Horsens. Phuc works in a restricted palette of black and white in different mediums—ceramics, painting, and drawing—and with communities in countries that include Ghana, Japan, and the US. There he helps people to tell their stories through collaborative “social design thinking” projects, but he has returned to Vietnam for the first time in over ten years to trace his own personal history.

Having followed his work for some time, Vietcetera finally had the chance to meet with Phuc Van Dang during his visit to Ho Chi Minh City. We learned about his life lived in black and white, and how he is creating and curating his own and other people’s memories.

How would you describe what you do?

I’m a visual storyteller and a conceptual artist—I love to realize concepts. And I love to make deep connections to the communities I work with by engaging in projects that I would define as “social design thinking.” I want to help communities to become more creative.The artworks have to be meaningful within their context. To me, that’s very different from creating trendy street art. This process usually starts with a workshop. I learn about the place and its history. I encourage people to draw or write what is relevant or personal to them—and we develop that into a visual project. It’s not about me and my artistic practice, it’s about helping them to realize their world which I help to curate.

We read that you live in a converted prison in the central Danish city of Horsens. How is life in Denmark different to growing up here in Vietnam? What’s life like working out of a former prison?

Denmark is a small but very creative place for art and design with lots of government funding for those industries. It also has a long history of storytellers like Hans Christian Andersen. There, I live in a town called Horsens. Since 2006, Horsens’ Faengslet prison has become a cultural center with a museum, shops, offices, and places for people to stay. In the grounds, they’ve also held concerts by bands like Metallica and Rammstein.

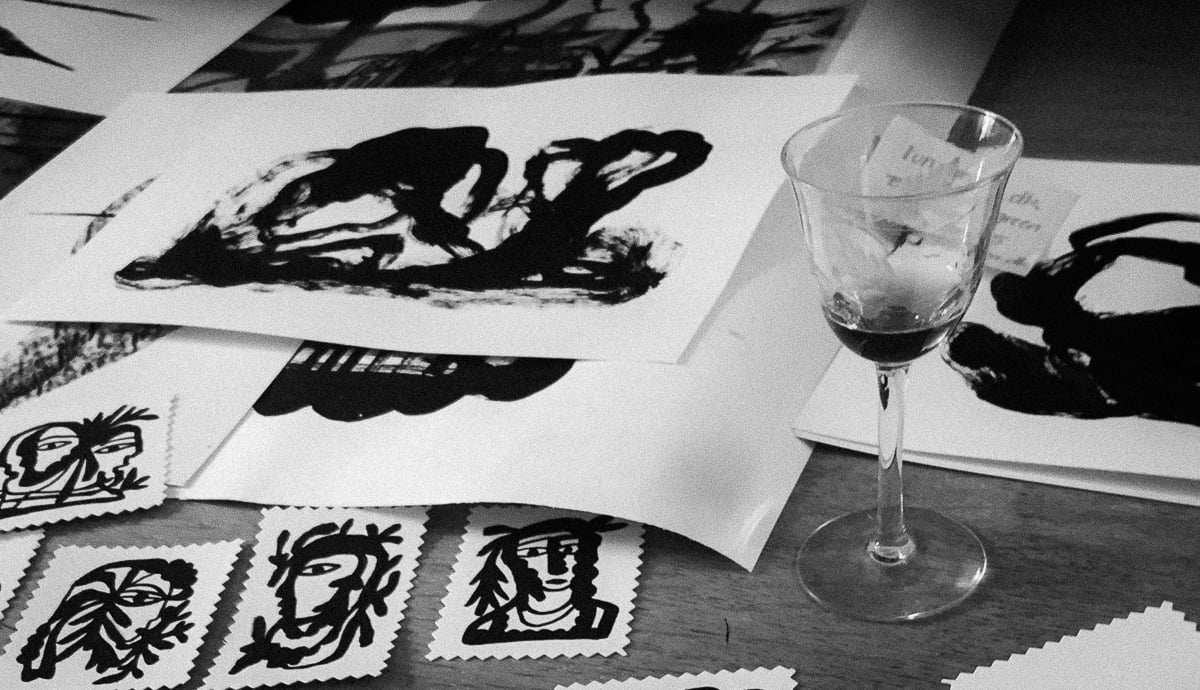

I have a room in the prison which is my art studio. My room is called “Husflid,” which means “Crafts.” It used to be where the prisoners would go to make things. Inside there’s just a table with some vintage books and my sketches everywhere. It looks chaotic but to me, it feels peaceful. Through the window, I can see the world outside. The prison bars, I think, protect me from the system—in my studio there is no system, just artistic freedom.

In your own work and in the images you share on social media, you restrict yourself to black and white. Can you tell us why?

I’ve worked in black and white for the past six years. Although it sounds restrictive, those boundaries make me feel content and they give me more power. Don’t forget black is a color too, and it just looks…sexier. It also reminds me of shadows—when the sun isn’t present, there is black. And if we stand in the shade, we’re all black too.

Besides their minimal, functional design aesthetic, Scandinavian countries seem to embrace darker cultural forces like death metal. Has that impacted your work?

For inspiration, I do listen to a lot of rock and roll. I like David Bowie, Nick Cave, and Kate Bush—anything deep and dark. When you read their lyrics, you realize they deeply understood life because they lived it fully. Some people are scared of darkness, but I’m not. People are scared of death too, but I think death is beautiful—if you don’t die, then you haven’t lived. In the same way, without unhappiness, we’d never know what it is like to be happy. This is what it means to be human. I also think every person has a devil inside them. It’s always there waiting for our acknowledgment. You might see that as something problematic or negative, but it’s not something to fear. It can give you energy if you control it effectively.

What is your working process like when you are at home in Horsens? What inspires you to draw?

When I’m at home, I wake up, put on some old vinyl records, and I light a candle to remind me that I’m alive. Then I drink a shot of port wine and I begin to work…

How would you define your nationality now?

I wouldn’t define myself as Danish or Vietnamese. I’m human and my heart beats just like yours. Knowing that I can adapt to any country I visit because beneath our cultural differences we have the same beating heart. That’s why my Instagram name is “Phucisme,” a shortened version of “Phuc is me,” because I’m just me. That’s all.

Which countries have you connected to most deeply?

Every year, I spend two weeks in Ghana. I go there to help people to think outside the box. Together we explore how drawing, painting, and making crafts, can be a business to lead them out of poverty. It gives them hope once they realize that with two hands they can create something from nothing. The people I have worked with there have since returned to more remote areas, and these ideas have spread organically.

What brought you back to Vietnam this time?

I haven’t been to Saigon for over ten years—the last time was around 2005. I didn’t feel comfortable here then. But I finally came back to work on some projects. During this trip, I have collaborated with my cousins at the handmade design label, TimTay, whose new collection’s pieces have my images embroidered on them. With Vietnamese artist LiarBen, I have completed a mural project in Binh Tan and a duo-show called “Coordinates of Time” at Chaosdowntown. It is part of curator Nhung Walsh’s Saigon Blueprint project. In this show, myself and Ben created an installation that describes our memories of this city, and my process included reconnecting with my 98-year-old grandmother.

Is it important for artists to maintain an underground sensibility?

When a young artist tells me they are underground, I ask them what that means. I draw a line—“here is the ground and this is under, so what’s above you?” And sometimes they don’t know, so how can they define themselves as underground? Also, I remind them not to be afraid of being overground. Commercial doesn’t necessarily mean bad. You can work in that sphere to help change their thinking.

Does working in the commercial sector require you to compromise?

Successfully working in the commercial sector requires dialogue. Through cooperation, you can work together to instill an underground aesthetic into that commercial space. However, companies sometimes hire famous artists to cache in on their fame. They want to be associated with the artist without understanding what they do. When I have worked on commercial projects, there have been times when the director has expressed a preference for me to use certain colors, or they have wanted me to follow certain trends. But I don’t follow trends, I create them.

Have you created your masterpiece yet?

My masterpiece is not a masterpiece in the traditional sense. It’s fragments—lots of small pieces of art spread around the world. It’s another reason that I don’t fear death. If I die tomorrow people will remember me because I gave them love through the realization of our artistic collaborations. I’m a poor artist in my pocket, but I’m rich in my heart. Anyway, money is just printed paper to which we ascribe value. You see the sunrise, nature, all this around us? You cannot pay for it with money. These human moments, they’re all free.