Film journalist Le Hong Lam’s passion for cinema began as a child when he saw Tran Khanh Du’s 1979 wartime drama “Mẹ Vắng Nhà” (When Mother’s Away), and blossomed through his teens with the help of pirated VHS tapes and mobile cinemas.

By paying heed to directors on TV and in print media, he gained a deeper understanding of the film world. When he majored in journalism at the Hanoi National University, Lam indulged his love for the film world by writing about it. “As a long time film journalist and a lifelong film-lover, I feel that my writing shows some sharp judgement, and I hope some style too,” Lam tells us.

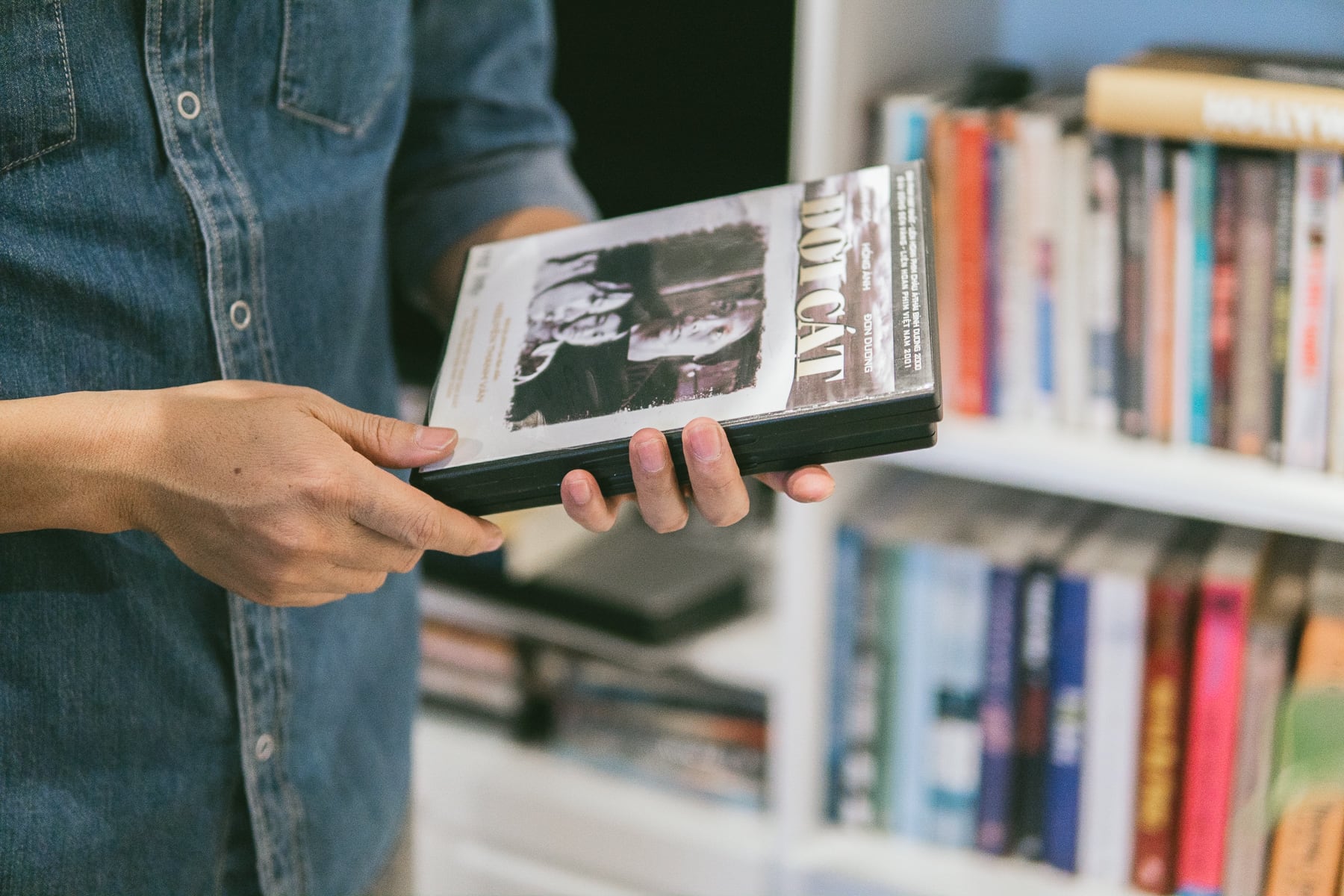

We’ve caught up with Lam after the launch of his new book, “101 Best Vietnamese Films” (101 Bộ phim Việt Nam Hay nhất), a comprehensive shortlist of Vietnam’s finest cinematic works from 1953 to 2018, which is unfortunately not yet available in English. Lam makes for entertaining company as he regales us with tales of his own affinity for film, the history of cinema in Vietnam and his hopes for its future.

Preserving Vietnamese cinema

Lam is well versed in film from all over the world, particularly the West. He believes this has granted him a good perspective to observe and critique films from his native country. While western-made films receive the most attention and praise worldwide, Lam says his first love has always been Vietnamese films.

“I can feel the soul in Vietnamese films,” he tells us, “I can identify with the characters and the historical context, that’s the reason a good Vietnamese film touches my soul more than any foreign movie.”

Speaking on the downfalls of cinema in Vietnam, Lam believes that more can be done to preserve and protect items of heritage in the industry. This is the very reason that he decided to publish “101 Best Vietnamese Films”. He wants young readers to be able to easily learn about Vietnamese films from the past, to appreciate movies that have caused a stir at international film festivals, and to develop a more detailed understanding of the different periods in Vietnamese cinema.

The ups and downs of Vietnamese film

“Old Vietnamese movies, before the 1970s, might be considered boring or confusing these days, mostly documentary about the war. They’re very dialogue heavy, with lots of sublimated scenes and nuanced dips between fantasy and reality. This kind of set-play was repeated so continuously for a while.” Lam informs us, “But in the middle period, the 70s, 80s, and 90s, the life flow of Vietnamese film gets really interesting.”

Lam pauses for a moment to gather his thoughts, then launches into a verbal highlight reel of Vietnamese cinema from the 1970s until the present day.

The 70s

“Before reunification in 1975, the North was famous for epic films such as “The Little Girl of Hanoi” (Em Bé Hà Nội, 1974), and “17th Parallel, Nights and Days” (Vĩ Tuyến 17 Ngày và Đêm, 1972). These were strong in plot and content, and focused mainly on the stories in war.”

“Meanwhile, the Southern film industry was enjoying great success, entertaining mass audiences in a variety of genres, from Vietnam’s first horror flick “The Ghost of the Hua Family” (Con Ma Nhà Họ Hứa, 1972), to comedies like “Five Bumpkins” (Năm Vua Hề Về Làng, 1974) and “Four Oddballs of Saigon” (Tứ Quái Sài Gòn, 1973). These were all hit movies, and attracted large audiences to the theater. Also at that time, Hong Kong martial arts films were hugely popular, so a lot of filmmakers went in that direction too.”

Into the 80s

The late 70s and early 80s was a golden period for Vietnamese film. Nguyen Hong Sen’s “The Abandoned Field: Free Fire Zone” (Cánh Đồng Hoang, 1979) took home the Golden Prize and the Prix FIPRESCI at the 12th Moscow International Film Festival. Other celebrated movies from these years include “When Mother’s Away” (Mẹ Vắng Nhà, 1979), and Dang Nhat Minh’s excellent “When The Tenth Month Comes” (Bao Giờ Cho Đến Tháng Mười, 1984), which was picked as the best Asian films of all time by CNN.

After the end of the war in 1975, the new regime agreed to bring about changes in Vietnamese cinema. Directors were encouraged to move away from the propagandic documentary style that had been used during the war years.

“Looking back at that time now, the cinematography and acting were good, but perhaps the directors were quite rudimentary and naive. By the 80s they had begun to mature, to escape propaganda and find a way to tell new stories which critiqued the Vietnamese society,” says Lam.

The 1990s and the decline of Vietnamese cinema

“State-funded movies in the 1990s contained some important works, like “Sandy Lives” (Đời Cát, 1999), “The Deserted Valley” (Thung Lũng Hoang Vắng, 2001). Meanwhile, members of the Vietnamese diaspora, or Việt Kiều, were returning to the country to make movies like “The Scent of Green Papaya” (Mùi Đu Đủ Xanh, 1993) and “Cyclo” (Xích Lô, 1995), both directed by Tran Anh Hung, as well as Tony Bui’s “Three Seasons” (Ba Mùa, 1999) which starred Harvey Keitel. “Because of this new international influence on Vietnamese film, the 1990s became quite a prominent period,” Lam observes.

“But it wouldn’t last,” Lam tells us. “Filmmakers eased off in their efforts in the late 1990s, and contemporary Vietnamese cinema fell into a rut. State-run movies had grown predictable, and films about the war were being overdone. By the late 90s and early 2000s, old theaters had almost disappeared, being turned into bars and pubs, discos and concert halls!”

Lam laments, “Within six or seven years, cinema just about died.”

The 2000s: The Rebirth of Vietnamese Film

“But around 2004, it began to recover.” Lam tells us about his delight at seeing director Le Hoang’s controversial film “Bar Girls” (Gái Nhảy, 2003). “Even though it was a state film, Le Hoang dared to explore the topic of escort girls – a topic that was quite sensitive in Vietnam at that time. Because of that film, there followed a wave of entertaining movies by the likes of Vu Ngoc Dang, Nguyen Quang Dung and plenty of others.”

“As you can see, cinema development is very strong now, the market is really wide open,” remarks Le Hong Lam in reference to the appearance of cinema chains like CGV, Galaxy, Cinestar and Lotte Cinema. Vietnam is a young nation, with about a half of the population below 30 years old, and since around 80% of cinema-goers are between 18 and 30, the Vietnamese cinema industry is considered a great prospect for trade.

“Filmmakers are in a race to box office success. To make a blockbuster, producers and directors have to appeal to the tastes of the mass audience. Entertainment is of course the most important factor, and therefore about 80% of contemporary Vietnamese films could be considered mainstream or pop movies,” concludes Lam when talking about the current film market.

But there’s still room for alternative styles. He goes on, “Artistic and experimental movies still need to be made, and directors must still try to make an impression. This makes the ecosystem of the cinema more diverse and interesting. Until 2018, Vietnamese film was growing in quite a unidirectional way, but some diversity will make it healthier.”

2018: A pivotal year for Vietnamese cinema

“But in 2018, I noticed that Vietnamese film began to diversify.” Lam name checks Cao Thuy Nhi’s “Nhắm Mắt Thấy Mùa Hè”, a romantic drama set in Japan. From his point of view, the independence of thought with which it was produced makes it a breakthrough movie.

Leon Le’s “Song Lang” warranted high praise upon its release in August 2018, as did the 2015 documentary series “Finding Phong”, a joint effort by Tran Phuong Thao and French director Swann Dubus. Critically acclaimed titles like these, in Lam’s eyes, are what really make the Vietnamese film market colorful, as opposed to purely commercial films.

“Maybe 2018 was a pivotal year for us, and in years to come we will see more works of this ilk.” Lam speculates, “As someone who is deeply entrenched in Vietnamese film, when I look at the signs, I feel quite optimistic. As the market grows, so too do the tastes of the audiences in Vietnam. Surely the result of this will be opportunities to see many different kinds of movies.”

Movies and cultural heritage

Movies are identified as a cultural heritage. But sadly, they’re still something unappreciated in Vietnam. That’s the reason why “101 Best Vietnamese Movies” was born. Each meticulously curated title is written by Le Hong Lam with warmth and affection. Altogether they provide a panoramic view of the life of Vietnamese film.

Talking about what’s next, Lam intends to complete two more projects on Vietnamese cinema. The first, a body of research on cinema in Saigon before 1975, through which he hopes to re-educate people on movies which were forgotten about after Reunification.

Second, a book which biographies Vietnamese actors of the past.

“I want to meet them, hear their stories of how the films were made, to celebrate their work. These actors aren’t given enough credit,” Lam tells us, “but they are great and important artists. By publishing a book on them, we’ll be preserving not only the actors, but their memories of Vietnamese cinema.”

Related Content:

[Article] “Song Lang” By Leon Le Is A Film About Cassette Tapes, Cai Luong, And Love

[Article] Charlie Nguyen In Five Films According To The Vietnamese Director